Diving Deeper into Operating Systems – Part 0

By Mazdak Pakaghideh • 6 minutes read •

Have you ever wondered how do computers boot up? How does the computer find the operating system when there is none present? Or even how an operating system is developed? These questions intrigued me when I started learning programming. I pondered, whether is it possible for a simple calculator app to function standalone without an underlying operating system.

Well to find out, we’ll first need to study the fundamental concepts of computers.

If you wish to make an apple pie from scratch, you must first invent the universe.

Carl Sagan, American astronomer and planetary scientist.

The OS

We are all accustomed to using various operating systems (OS) for daily tasks or leisure activities. But what exactly are these operating systems, and what do they do? An OS creates an interface that allows the software to effectively utilize the necessary hardware and resources. To visualize this, let’s examine the structure of Atari’s consoles.

In an old Atari console, when you insert a disk, that disk has complete access to the hardware. Essentially, the disk acts as both the operating system and the only running game. There’s no interface for managing multiple applications, multi-threading, or RAM. If you want to run another game, you need to turn off the console and switch the disk. Therefore, developing a game for Atari means directly controlling the hardware with your code.

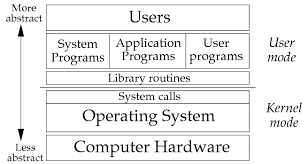

Contrast this with modern operating systems, which have a structure like the one shown below:

By minnie.tuhs.org

By minnie.tuhs.org

in modern systems, the kernel manages both applications and hardware. Applications cannot directly access the hardware; instead, they communicate with the hardware through the kernel. This is why you cannot create an OS with high-level languages like Python, as they don’t provide direct hardware access. Instead, high-level languages allow you to call predefined APIs that abstract hardware interactions.

What is The Kernel?

The kernel is the heart of an operating system. It manages memory, the hard drive, and other hardware components. However, it’s useless without a set of applications. In summary, an operating system is composed of the kernel and a collection of applications that users can interact with.

A perfect example of this concept is the GNU/Linux project. Richard Stallman, founder of the Free Software Foundation, initiated the GNU project, which stands for “GNU is not Unix.” Stallman believed that to create a society of free software, the most essential application needed was the operating system itself. He began developing essential tools like the Emacs text editor and the GCC compiler. While these were crucial components, the project lacked a kernel.

This changed when Linus Torvalds released the Linux kernel. The combination of the GNU system and the Linux kernel resulted in a complete, free operating system known today as GNU/Linux.

Developing an Operating System

While creating an operating system as complex as macOS, Linux, or Windows is extremely challenging, understanding the basics is within our reach.

If you are unable to create something from scratch, you can never understand it.

The BIOS

BIOS stands for Basic Input/Output System, a program running on a computer’s motherboard. It initializes hardware components during the boot process and provides basic instructions that allow the operating system to start. The BIOS also offers a low-level interface for communicating with hardware components, such as hard drives and keyboards.

The Boot Process

When a computer starts up, the BIOS doesn’t know how to load the operating system and requires a boot sector to do so. However, since there is no operating system, there is no path to the boot sector. To load it, the BIOS must know the physical location of the boot sector on the disk, which is cylinder 0, head 0, sector 0, and it’s 512 bytes in size.

By web.cs.ucla.edu

By web.cs.ucla.edu

To ensure that a disk is bootable, the BIOS checks for a specific signature. Specifically, the 511th and 512th bytes of the boot sector must be 0xAA55

The BIOS Interrupts

BIOS interrupts are software interrupts triggered by the BIOS during the boot process. These interrupts allow the BIOS to communicate with the operating system and other software. They perform tasks such as reading from or writing to disk, initializing hardware components, and carrying out low-level system functions. When an interrupt is triggered, the processor stops executing the current program and switches to the interrupt handler—a special routine that performs the required task before returning control to the main program.

The CPU Registers

CPU registers are small, high-speed storage locations within the CPU used to hold data that is being processed or manipulated. They function similarly to RAM but are faster and more temporary. Registers are typically measured in bits, such as 8-bit or 32-bit registers, and store memory addresses, data being processed, and status information. Registers are a crucial component of a computer’s architecture, enabling fast access to frequently used data and significantly improving performance.

The Code

Writing the boot sector requires using assembly language. It’s important to note that this code must be written and compiled for the target computer architecture. For instance, you cannot run this code on an ARM-based Raspberry Pi because it is coded in x86 assembly for x86 computers.

A Simple Boot Sector in Assembly x86

jmp $ ;Jump to the current address (Infinite loop) ****

; Fill with 510 zeros minus the size of the previous code

times 510-($-$$) db 0

; the previously mentioned BIOS signature

dw 0xaa55

Hello World !

In order to print a single character we use the BIOS interrupt0x10which is responsible for various video services.

withAHset to0x0E(tty mode) andALset to the ASCII value of the character to be displayed, a single character will be displayed on the screen.

Basically the interrupt0x10reads theAXregister which is 16-bit register consisted ofAH:AL.

;helloworld.asm

mov ah, 0x0e ; tty mode

mov al, 'H'

int 0x10

mov al, 'e'

int 0x10

mov al, 'l'

int 0x10

int 0x10 ; 'l' is still on al, remember?

mov al, 'o'

int 0x10

mov al, ' '

int 0x10

mov al, 'W'

int 0x10

mov al, 'o'

int 0x10

mov al, 'r'

int 0x10

mov al, 'l'

int 0x10

mov al, 'd'

int 0x10

mov al, '!'

int 0x10

jmp $ ; jump to current address (infinite loop)

times 510 - ($-$$) db 0

dw 0xaa55

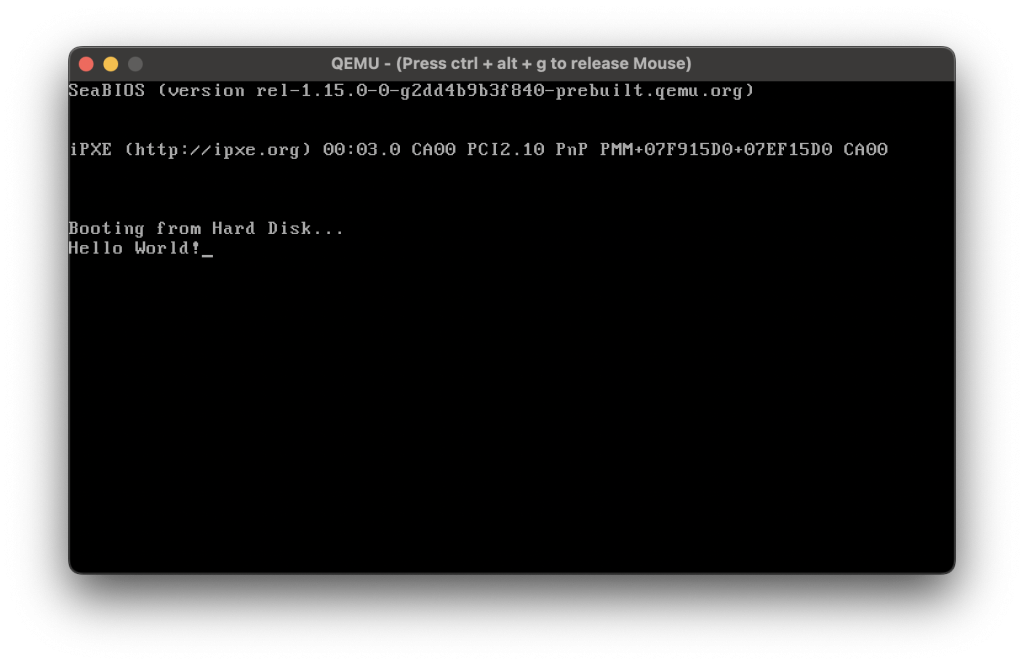

Compiling and Testing

While it’s possible to create an .iso file and boot this boot sector directly, it’s not recommended for beginners. Instead, we will use QEMU for emulation and NASM as the assembler.

$ brew install nasm qemu #macOS

$ sudo pacman -S qemu nasm #ArchLinux

$ sudo apt-get install qemu-system nasm #Debian/Ubuntu

and then we proceed to test our Hello World boot sector:

$ nasm -f bin helloworld.asm -o helloworld.bin

$ qemu helloworld.bin

Note: on some systems you may need to use qemu-system-x86_64 command.

If everything goes well, you should see a window like this:

References

- How Computers Really Work by Matthew Justice

- wikipedia.org

- github.com/cfenollosa/os-tutorial/

- www.cs.bham.ac.uk

- wiki.osdev.org

- littleosbook.github.io

- web.archive.org

- rocket.ir

The post Diving Deeper into Operating Systems – Part 0 appeared first on mazdak.dev.

Comments

You can comment on this blog post by publicly replying to this post using a Mastodon or other ActivityPub/Fediverse account. Known non-private replies are displayed below.